The intersection of crypto & the creator economy

A deep dive into the creator economy and the mind of Li Jin

Crypto Rabbit Holes is a space for me to slow down and pay closer attention to what’s happening and what I’m learning in the crazy, fast-moving world of crypto. If you aren’t subscribed, you can do so here:

Read Time: ~25 minutes

The world of crypto seems to purely be filled with hype and speculation. It's great (and totally crazy) that people are making life-changing amounts of money selling pictures on the internet, but what's the point of it all? What tangible value does crypto have?

One of the loud pro-crypto narratives is that it's great for creators of all kinds, and for their fans. If you explore this argument, you'll end up hearing terms like: creator economy and passion economy. If you follow the people talking about them, you'll inevitably find your way to Li Jin.

This is Li's vision of the world:

A world in which people are able to do what they love for a living and to have a more fulfilling and purposeful life (source: Atelier Ventures)

She is widely considered as one of the go-to people thinking and writing about being a creator on the internet. I went down a deep rabbit hole consuming her many interviews and writing. One thing stood out to me: crypto can help us build a world where we're all earning income and ownership from our contributions online.

To appreciate the value of crypto for creators and fans, we need to walk through the challenges and opportunities that creators have faced throughout history. I'll draw heavily* from the wisdom of Li Jin to tell you the story of the creator economy and how it's developed.

*I take no credit for the ideas in this article - the entire piece is mostly a reproduction of Li's ideas. I've attempted to piece them together in a logical and digestible narrative, to understand the creator economy and where crypto fits in. If these ideas resonate with you, I highly recommend listening to Li's interviews or reading her writing.

Anyway, before we explore her ideas, let's get to know Li Jin.

Who is Li Jin?

Li is from a first-generation immigrant family. She was born in Beijing, China and moved to the US when she was 6. Growing up, she faced a recurring battle between creativity and the practical need to support herself financially. She loved historical fiction and Victorian novels, but her mum told her she was wasting time reading novels instead of non-fiction. She enjoyed writing fiction and poetry, or making crafts, but didn't see how she could monetise those interests.

When she was 17, she had to decide between pursuing her love of painting through art school or going to traditional college. She says: "Harvard—and the promise of financial security—was my parents' dream as much as mine. I went, and the rest is history."

After graduating from Harvard, she worked in corporate strategy and product management before joining a16z, a venture capital firm, as a consumer investor in 2016. Since joining a16z, Li has focused on investing in the people and companies building towards her vision of the world.

After leaving a16z, she started Atelier Ventures, her own early stage venture fund, which has now merged with Variant Fund, where Li is the co-founder and General Partner. Variant is a crypto fund investing in a "world in which everyone becomes an owner of the products and services that they use"

Through her writing and investing, Li is building a world in which her younger self could have confidently chosen art school over Harvard. Fittingly, she's become a creator herself. She has taught an online course, writes a newsletter, hosts a podcast, creates TikTok videos, and sells her own NFTs (in collaboration with her childhood best friend).

With that in mind, let's dive in.

What is the creator economy?

First, we need to break down what creator economy means:

A creator is a broad term, so we’ll be limiting the scope of that to mean anyone who uploads their own content online. To be more specific, we can also define sub-categories of creators based on variables like the platforms they use, the content type they create, and the industry verticals they operate in. For example: a fitness instructor who shares instructional videos on Youtube, or a digital artist uploading images of their art on Instagram.

The economy in the creator economy is about how individuals can monetise their creations.

Li describes the evolution of the creator economy in 4 different phases. Here's the short version:

Creator Economy 1.0 - enabled by the launch of the internet, individuals can become creators.

Creator Economy 2.0 - creators leverage their reach on platforms and monetise through advertising and brand sponsorships. We'll explore the problems that emerged from ad-based business models.

Creator Economy 3.0 - creators become independent businesses and are empowered to monetise directly from their fans. This is the chunkiest part of this article where we explore: the Passion Economy, how to build a creator middle class, 100 True Fans and the role of crypto.

Creator Economy 4.0 - creators and their fans co-create and build wealth together. This is our glimpse into the future of the creator economy.

It's important to note that each phase of the creator economy is additive to the previous. Each phase gives creators new options - with new sources of income, new ways of doing business and new ways of connecting with fans. Creators have the flexibility to mix and match these options to suit their needs.

Creator Economy 1.0 - the rise of creators

Li Jin: "Creator Economy 1.0, which was the dawn of the creator economy, I think of as existing as long as the internet has existed so initially people were uploading content online. They were doing so on their own independent websites or blogs that they set up. And then as the social networks started to come out, people also utilised those for content creation. In those days, I would consider everyone to have been a content creator as long as they posting content but it was very nascent in terms of the economy piece of the content creation. (source: How To Own The Internet | Bankless)

The creator economy started with the launch of the internet. It enabled anyone to upload their own content online and become a creator. This started with personal websites, and quickly turned into social media and user-generated content platforms like MySpace, Flickr, Facebook, Reddit and many others. As Li says, the "economy" was missing, because it was difficult to collect payments online.

This was partly because payments weren't built directly into internet browsers. Marc Andreessen, the co-founder of Netscape (one of the first internet browsers) and a16z, describes this as the "original sin of the internet" (source: a16z Podcast: From the Internet’s Past to the Future of Crypto).

He argues that the missing payments functionality led to the internet we have today where business models online are predominately ad-based. Because of this sin, we have all the downstream concerns around privacy, data collection and a misalignment of incentives between platforms that are reliant on ad revenues, and the needs of their users.

Creator Economy 2.0 - the monetisation of attention

Li Jin: Creator Economy 2.0 was the burgeoning economy around people who built up fame and influence on all of those channels. Gradually, you had people who accumulated audiences by posting content on the internet. They were kind of like digital native celebrities. This influential class then began to receive monetisation, usually in the form of advertising or brand sponsorship. So they monetised the eyeballs and reach that they got from their total audience, and that was a game that really rewarded reach and scale. (source: How To Own The Internet | Bankless)

The rise of platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Youtube allowed creators to monetise at scale, through ads and brand sponsorships. The platforms aggregated the overwhelming amount of content online, and transformed the messiness of the internet into easy-to-use applications. This was great for creators and their fans. Creators could more easily create content, build a large audience and monetise their attention. Meanwhile, fans could easily discover and consume the content of their favourite creators at no monetary cost.

Despite these upsides, a number of issues emerged:

To monetise as much as possible, creators needed to build the the largest possible audience. This incentivised the creation of viral and attention-grabbing content, over niche content.

Li Jin: The biggest impact of the web2 internet may be the creators who don’t exist and the creations that were never made because they have no viable business model. (source: The Web3 Renaissance: A Golden Age for Content)

Building a large audience involves accruing as much attention as possible. Given attention is limited, and algorithmic feeds of platforms favour creators who have the attention, the outcome is that only a small number of creators rise to the top and make a living. Meanwhile, the rest of the creators, who Li calls "long-tail creators" are barely getting by.

Li Jin: On the web2 passion economy platforms - a very small sliver of creators are actually able to make a full time living salary and everyone is cobbling together a little side income that supplements their day job. (source: What Is The Creator Economy? | Bankless) On Spotify, for instance, the top 43,000 artists—roughly 1.4% of those on the platform—pull in 90% of royalties and make, on average, $22,395 per artist per quarter. The rest of its 3 million creators, or 98.6% of its artists, made just $36 per artist per quarter. (source: Building the Middle Class of the Creator Economy)

there is a power imbalance between web2 platforms and their creators. While the success of creators brings value to platforms, creators are passive recipients of the decisions of platforms. The platforms have the power to make decisions which can have major impacts on the livelihoods of creators - for example, changing how and how much creators are paid, or even choosing to remove them from the platform entirely. This is problematic because creators build a reliance on platforms for distribution of their content and access to their audience. To make things worse, creators are often locked into platforms because their data, including the details of their audience, are locked behind siloed databases of individual platforms.

LI Jin: All of the current centralised creator platforms have a tension between empowering and disenfranchising creators. At the end of the day, creators are building their businesses on rented lands when they're building on web2 platforms. (source: What Is The Creator Economy? | Bankless)

Creator Economy 3.0 - the monetisation of individuality and passion

Li Jin: Creator Economy 3.0, a phase in which creators aren't only conduits for selling other people's businesses and brands but instead are regarding themselves as the brand and business and are trying to monetise their own persona in different ways. They're doing so increasing by using lots of different tools and platforms that have flourished in the last couple of years all really based on the direct monetisation of their super fans. That's the phase we're in now, creator economy 3.0 which is creators as their own independent businesses. NFTs, I would bucket under that third phrase, it's another tool in the toolkit for direct monetisation of fans. (source: How To Own The Internet | Bankless)

The underlying theme of Creator Economy 3.0 is the increasing ease and ability for creators to be paid directly by their fans.

This phase was sparked by two big changes:

the rise of new digital platforms like Skillshare and Substack created new, more accessible forms of revenue; and

tools like Webflow and Stir simplified the process of creating and running online businesses, lowering the barrier to entry.

Together, these tools and business models unlocked the possibility for more individuals to monetise their unique skills, knowledge and passions - this is Li's vision of a Passion Economy.

More specifically, it means existing creators don't need to solely rely on web2 platforms for distribution and ad-based revenue. For example, Ali Abdaal is a Youtuber who teaches about topics like productivity. In this video he breaks down how much earned in 2021: ~$390,000 from YouTube ad revenues, and ~$716,000 from online courses he'd published to Skillshare.

Another exciting implication is that individuals like Li, who previously didn't see a pathway to monetising their passions and niche interests, can now do so. This is also great for us, as consumers, because it makes it easier to discover the content and creators aligned to our preferences. A great example is David Perell, who tapped into the niche of teaching people how to write online and build an audience.

However, as we know, there's difference between being ability to monetise, and being able to make a living. In Creator Economy 2.0, most creators were "cobbling together a little side income". It's arguably inevitable to have inequality in the creator economy, given creators are leveraging their uniqueness to build loyal fan bases, and aren't easily substitutable. However, the Passion Economy won't exist at scale if success is only concentrated at the very top.

In Building the Middle Class of the Creator Economy, Li argues that just like in the real world, we need a healthy middle class of creators; the middle class being "those that aren’t household names but have a solid base of customers who provide the foundation for a decent income."

Li Jin: The sustainability of nations and the defensibility of platforms is better when wealth isn’t concentrated in the top 1%. In the real world, a healthy middle class is critical for promoting societal trust, providing a stable source of demand for products and services, and driving innovation. (source: Building the Middle Class of the Creator Economy)

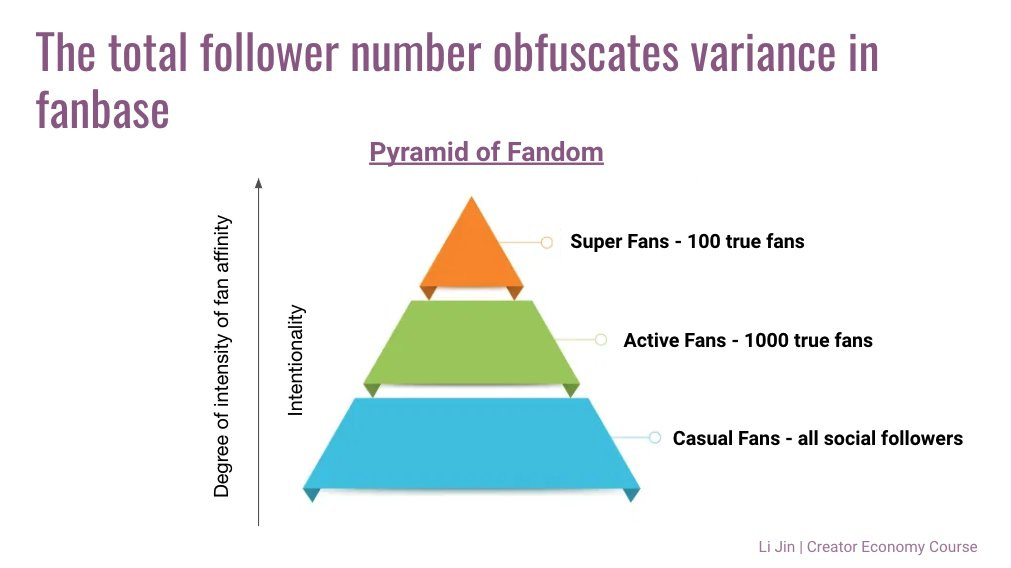

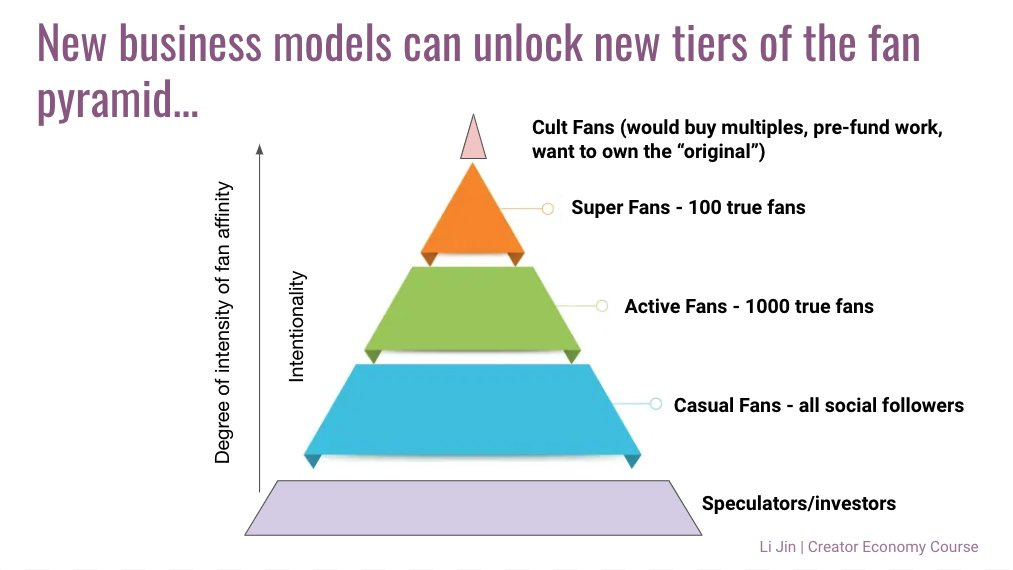

One way this could be possible, is if creators find their 100 True Fans; this is Li's adaptation of Kevin Kelley's original 1000 True Fans concept:

Kevin Kelley: To be a successful creator you don’t need millions. You don’t need millions of dollars or millions of customers, millions of clients or millions of fans. To make a living as a craftsperson, photographer, musician, designer, author, animator, app maker, entrepreneur, or inventor you need only thousands of true fans. A true fan is defined as a fan that will buy anything you produce. The number 1,000 is not absolute. Its significance is in its rough order of magnitude — three orders less than a million. (source: 1000 True Fans)

Kevin suggested that creators don't need large scale and reach, so long as they can monetise directly from 1000 true fans who purchase anything they produce. The 1000 figure is based on the hypothetical scenario where 1000 true fans pay the creator $100 a year, allowing them to earn an annual income of $100,000.

The numbers don't matter, so don't get caught up in it. The point to takeaway is that creators can make a living even if they have a relatively small, niche following. This makes building the middle class of creators much more achievable.

Li expands on this idea and suggests that creators may need even fewer fans - 100, rather than 1000:

Li Jin: I believe that creators need to amass only 100 True Fans—not 1,000—paying them $1,000 a year, not $100. Today, creators can effectively make more money off fewer fans. Now, 100 True Fans and 1,000 True Fans aren’t mutually exclusive, and the revenue benchmark of $1,000 per fan per year isn’t intended to be an exact prescription. Instead, this thinking provides a framework for the future of the Passion Economy: creators can segment their audiences and offer tailored products and services at varying price points. (source: 1000 True Fans? Try 100)

The basis of this theory is that creators can offer additional value to what Li calls super fans. Examples of this include: premium content, access to a community or even exclusive access to the creator’s time or expertise. By doing so, creators can convince their super fans to pay more. In Li's hypothetical scenario, the 100 fans pay the creator $1000 a year, rather than $100.

Again, the numbers don't matter. The point is that creators can make most of their living from a small number of deeply engaged fans, with a high willingness to pay. However, this isn't easy - creators need to deliver a lot more value to fans to justify higher prices. While this may sound too good to be true, it's already happening:

Li Jin: One creator on Teachable who advises artists on how to sell their art made $110,000 last year with only 76 students, at an average of $1,437 per course. Another creator who teaches physiotherapy made $141,000 with only 61 students, at an average price point of $2,314 per course (source: 1000 True Fans? Try 100)

In summary, new digital platforms and tools kicked off Creator Economy 3.0, allowing many creators the opportunity to make a living by monetising their passion and individuality. We’ll call this Part 1 of Creator Economy 3.0.

Part 2, is where crypto finally enters the story to open up possibilities of a supercharged creator economy. With crypto: creators gain new earning opportunities, more power and freedom.

One of the core benefits of crypto is the introduction of digital scarcity through tokens. Without crypto, there's no concept of digital scarcity for digital content. Everything can be reproduced, which means creators have a limited ability to sell digital goods. They've found ways around this by approximating scarcity, for example, by selling paywalled content (e.g. e-books or albums). However, the underlying content can easily be copied and redistributed for free.

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) allow us to represent digital assets online, so that we can own things on the internet. With NFTs, we can verify ownership (who owns a digital asset?), and authenticity (do they own the real thing?). This is powerful because:

it opens up possibilities for more individuals to monetise their creations, like Monica Rizzolli, a digital artist who received millions from selling her generative art collection, ‘Fragments of an Infinite Field'.

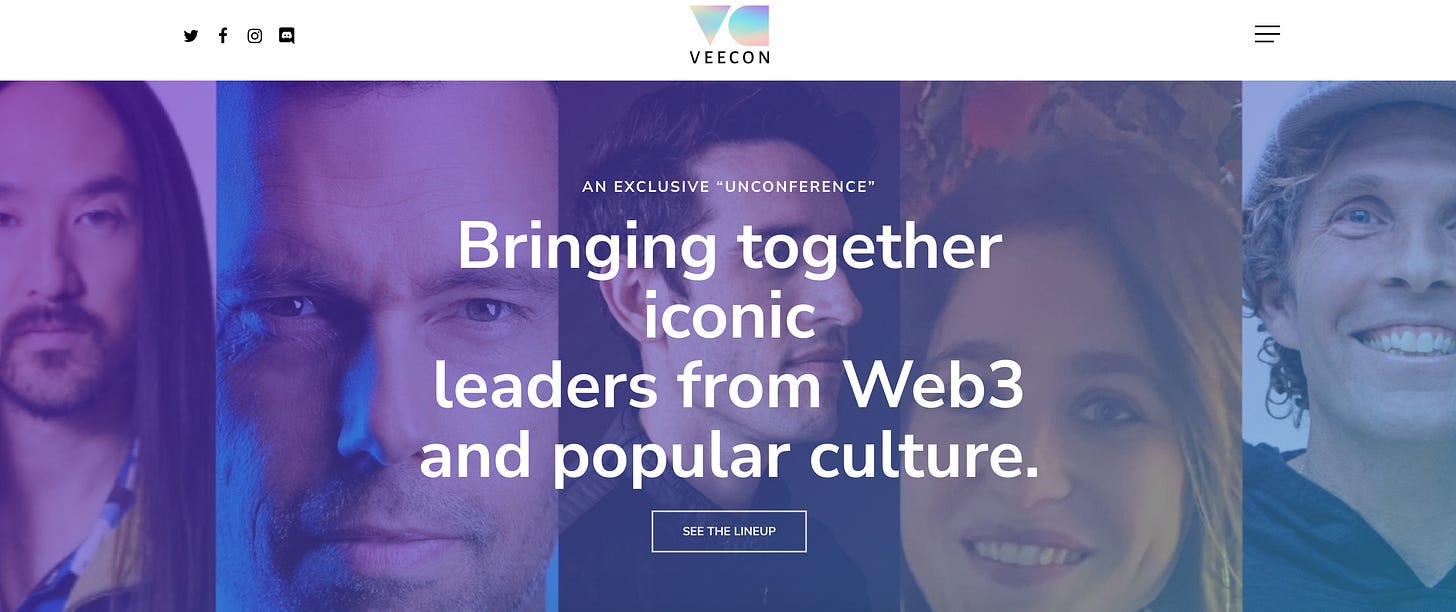

Fragments of an Infinite Field #814 (source) creators can easily verify who owns their assets, which allows them to deliver deeper value to those owners. The possibles are endless. Gary Vaynerchuk created VeeCon, a multi-day, in person conference which can only be attended by individuals who own an NFT from his VeeFriends collection.

VeeCon, described as “a first of its kind NFT ticketed conference for the Web3 community to come together and build lasting friendships, share ideas, and learn together.” (source)

Note: For an introduction to NFTs, see my summary of Chris Dixon and Naval Ravikant on The Tim Ferriss Show

The introduction of digital scarcity through NFTs has had an interesting impact on creator-fan relationships. Given NFTs can be freely traded on marketplaces, fans have become economically aligned with creator's and can profit from a creator's success. Jesse Walden calls this patronage+; where fans not only support creators out of an altruistic desire, but also out of self-interest for financial upside.

There are many flow-on benefits of this:

there are more people willing to support creators, including a new fan segment of speculators looking for profit

fans (including speculators) are incentivised to help creators succeed, e.g. by sharing their work, given the creator's success is their profit

fans can publicly showcase their varying degrees of fandom, and creators can capture their fans' full willingness to pay. XCOPY, one of the most popular crypto artists, has sold 1/1 NFTs (where only 1 exists) for millions, but fans can also purchase editions of his art (where there is a fixed supply, e.g. 750, of identical pieces) for thousands

creators can tap into what Li calls cult fans. They're the ones who spend seemingly illogical amounts of money, e.g. to buy the 1/1 art or own the "original". Rather than 100 True Fans, creators may only need a handful of cult fans to make a living.

Another benefit of crypto is the ability to fairly distribute value to those who create it. There's a few angles to this point:

even though content creation is often a collaborative process, there's no easy way to track and reward collaborators. One way crypto solves for this is through automated revenue splits, allowing creators to pre-program revenue to be distributed amongst contributors. Packy McCormick, who writes a newsletter about business strategy and trends, sold one of his posts as an NFT. Using Mirror, he programmed the sale to split the revenue to 15 other individuals, whose work he referenced.

Packy’s NFT sold for 2.19 ETH ($5,742.79) and this was split with 15 other contributors (source) Li points out a trend in the developed world in which people are making more money from their capital (things that earn a return) compared to their labour. This worsens income equality as those with capital are getting wealthier than those who are working.

Li Jin: A world in which what people have is a bigger contributor to their wealth than what they have to actually contribute with their energy and effort, forebodes really badly for our society and puts us on a path towards more extreme income inequality, exacerbated through multiple generations. What I hope to see is that we make them one and the same, people who contribute labour can earn capital through that work so the relationship becomes indistinguishable. (source: How To Own The Internet | Bankless)

In the creator economy, we can think of creators as contributing labour, which creates value for platforms, and financially rewards the owners of those platforms. What if creators could be owners of platforms too? Ownership would provide another pathway to financial stability. The problem, as Li says, is that it's restricted "to a privileged set of individuals—whether on the basis of geography, network, expertise, access, or for regulatory reasons."

However, crypto breaks down these boundaries and makes it easy to distribute tokens which represent value and ownership. With crypto, creators can gain ownership of the products and services they use, simply through participation. One example of this is when SuperRare, an NFT marketplace, distributed a token to artists and collectors on their marketplace.

One individual was given tokens from SuperRare worth more than $100,000 at that point in time (source)

Jesse Walden articulates the value of crypto in opening up access to ownership well:

Jesse Walden: In web3 the opportunity is to build platforms and networks that are built, operated and actually owned by their users... it's now possible to move the value of ownership at the same scale and speed that we move informaiton. We know from Silicon Valley's history that ownership is a powerful incentive to get talented people to contribute to your thing... but it's not been possible to distribute that to everyone in the world... Crypto enables that because you can literally send value; tokens, which are packets of value, to anyone with an internet connection no matter where they are (source: What Is The Creator Economy? | Bankless)

So far, we've focused on monetisation option in Creator Economy 3.0, but making money is only one aspect of being a creator.

Li Jin: It’s not just about money: it’s about agency and autonomy, and having the opportunity to participate in decisions that directly impact your livelihood. It’s about breaking the unilateral power that platforms hold as centralized points of control in the ecosystem. (source: Legitimacy Lost)

In Creator Economy 2.0, creators had little freedom to move their content and audience without compromising their livelihoods, and held little power against the decisions of platforms.

This power imbalance shifted slightly in favour of creators as new digital platforms allowed in Creator Economy 3.0 allowed for open data, e.g. Substack lets writers export and take their subscriber list anywhere. Crypto supercharges this, given data sits in the open, stored on a public database. This gives creators total flexibility in how they want to use the data, and means creators aren't locked into platforms.

The larger shift in power will occur by making creators owners of the platforms they use. Fortunately, as we've discussed, crypto makes this easy. With ownership, creators are empowered to shape platform decisions and take control of their own experiences.

Creator Economy 4.0 - the future of the creator economy

Li Jin: Eventually, the next phase of the creator economy will be the dissolution of boundaries between who is a creator vs who is an audience member. It moves to this world where the audience co-creates with the creator and they're all part of a community driving value back to the collective output that they put out. In that world, everyone is compensated with a reward proportional to how much value they contributed. I call that the evolution of the creator economy to the community economy. That is the supercharged version of the creator economy. (source: How To Own The Internet | Bankless)

Li calls Creator Economy 4.0, the community economy. It's where creators will co-create with their fans, and build wealth together. This is enabled by crypto tokens aligning the incentives of creators and fans.

The key difference between this phase and Creator Economy 3.0, is that fans can be rewarded with income and ownership for their contributions to a creator's success. The rationale is that we don't want to recreate the power imbalance between platforms vs. creators, within the creators vs. fans dynamic.

One example of this is Shibuya, a “web3 video platform allowing users to engage, fund, vote on the outcome and become owners of long-form content.” The concept is that fans can purchase Producer Passes (which are NFTs), and use these to vote on the plot and decisions of characters in an episode of the animated show. By doing so, fans earn a $WRAB token, representing proportional ownership over a collection of NFTs.

Another example is mfers, a generative collection of hand-drawn stick figures, created by sartoshi. These were released with a CC0 license, meaning there are no copyrights over the collection. Anyone can use it for whatever they want. They can create and sell derivative artworks, create merchandise, write books or make animations. Those who own a mfers NFT have an incentive to increase the profile and appeal of the collection because that increases the value of their asset. However, nothing is stopping those who don’t own one to also co-create with the mfers community, and be rewarded.

sartoshi: there is no king, ruler, or defined roadmap--and mfers can build whatever they can think of with these mfers… mfers don’t need sartoshi’s approval or looking over their shoulder as they experiment and build. my view of what is most valuable for me to offer to mfer holders is to amplify the best of their ideas and creations to reach vastly greater audiences…and add value for holders when the opportunities strike, including linking with artists who might create other nfts for mfer holders to claim. (source: what are mfers)

So far, we’ve only gotten a small glimpse into what Creator Economy 4.0 may look like. It’ll be fun to see what comes next, and how we can all be rewarded for online contributions.

Li Jin: Every single person who uses the internet is a creator in their own unique ways, what changes in the future is that they're able to financially benefit from that. (source: How To Own The Internet | Bankless)

Ultimately, the developments in each new phase of the creator economy has helped solve problems of the past, with each phase giving creators new options. The happy ending of the story of the creator economy is a world in which Li's grand ambition for a Passion Economy to exist at scale, is realised. Crypto is the newest tool in the toolkit, which promises to help us get there.

We started the creator economy with the opportunity for anyone to be a creator, but with no pathway to monetisation. Now with crypto, Li is optimistic that we can build a world "in which everyone is earning some income and ownership from their contributions to the internet, so everyone becomes a part-creator." That’s a world I’m excited to live in.

Thanks for reading! What did you think of this post? I’d love to hear any thoughts or feedback you have.

This is an incredibly cohesive, well-written, and insightful overview. Thanks for putting this together :)